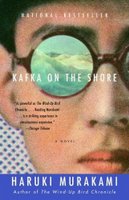

Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami

It’s hard to write reviews for good books without sounding like a paid-off jacket cover reviewer. Haruki Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore is one such book, that was a joy to read. I generally dislike reading translations and I don’t particularly like coming-of-age, voyage genres. But despite being both, Kafka on the Shore surpassed all my expectations and has become one of the most intriguing books I have read this year.

There's a scene somewhat early on that for me tipped the book from interesting to completely fascinating. Each subsequent scene was as gloriously strange, as unpredicatable as the fish that fall from the sky.

The scene involves cats, a dark and villianous Johnny Walker and the eating of the former by a grostequely snarky Walker. He eats their hearts to make a flute out of their souls which can be used to entrap larger, human souls. The passage is described with such clear-eyed bluntness that if it wasn't so skin-crawling, it would be really funny.

Set in

In a lot of ways, this book reminded me of Phil Robinson's 1989 movie Field of Dreams. Like the movie, Kafka on the Shore asks both his readers and the characters that populate the novel, to accept and trust the quirky mythology of Murakami’s world, without knowing any of the whys, whos and hows. And Murakami isn't too interested in making sure he answers all your questions either. Any second leeches could fall out of the sky, Colonel Sanders could tap you on your shoulders and lead you to your destiny (and a prostitute). And the woman you are in love with might be your mother...or your sister. Or not. You are compelled to keep reading if only to find out what the hell is going on.

Cleverly and with fascinating results, Murakami describes a world in which memories are tangible valuables that carry enormous powers. A body’s spirit can flit across our arbitrary notions of time, and sexuality is as potent and powerful a force as any on this earth. All of this makes this an understandably kooky book to read, while being completely endearing. After Kafka tells his librarian friend his secret fear that he might sleep with his mother, he replies,

"For a fifteen-yr-old who doesn't even shave yet, you're sure carrying a lot of baggage around."It's as if Murakami knows what you might be thinking, and he writes it up as dialogue instead of explaining. Similarly, there's a point when the librarian asks Kafka why he chose the infamous author's name as his pseudonym. There's a discussion about Franz Kafka's story, The Penal Colony, and an explanation given for his name. This happens often, where characters will somewhat abruptly have a seemingly tangential discussion about art, history, music and particularly Greek mythology. It adds an oddly informative, even worldly, feel to the book that is unusual and engrossing. It also exemplifies how nicely Murakami draws parallels and connections between wildly disjointed ideas and philosophies and creates his own reality and his own rules. Reading Murakami has that wonderful feeling that I sorely miss of stepping into a brand new world that is wholly unexpected in every way, each turn of events anticipated with delight.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home